Baleen whales are the titans of the ocean, the largest animals to have ever lived. The record holder is the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), which can reach lengths of up to 30 metres. That’s longer than a basketball court.

However, throughout their evolutionary history, most baleen whales were relatively much smaller, around five metres in length. While still big compared to most animals, for a baleen whale that’s quite small.

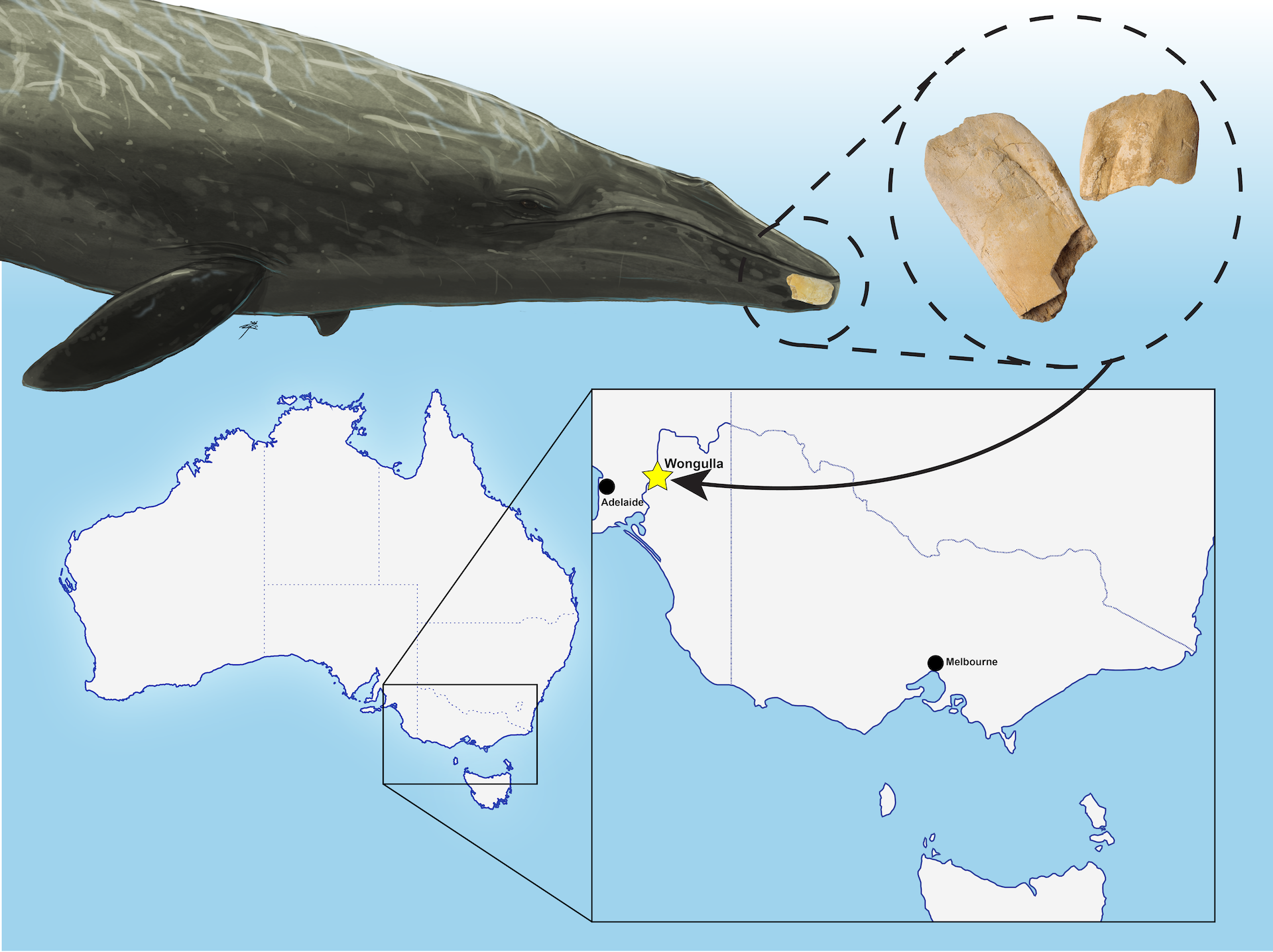

However, new fossil discoveries from the Southern Hemisphere are beginning to disrupt this story. The latest is an unassuming fossil from the banks of the Murray River in South Australia.

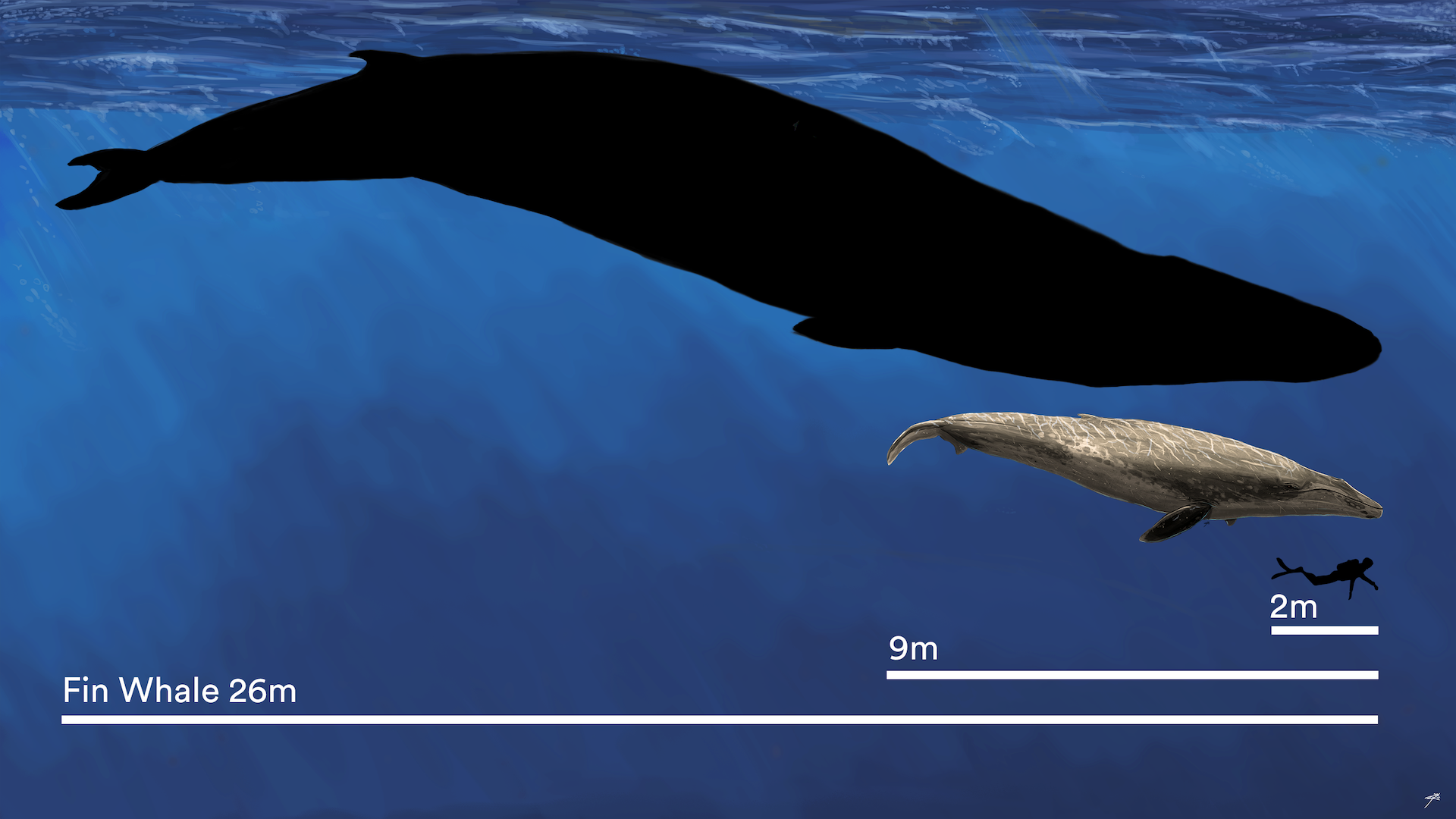

Roughly 19 million years old, this fossil is the tip of the lower jaws (or “chin”) of a baleen whale estimated to be around nine metres in length, which makes it the new record holder from its time. This find has been published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Art by Ruairidh Duncan

What are baleen whales?

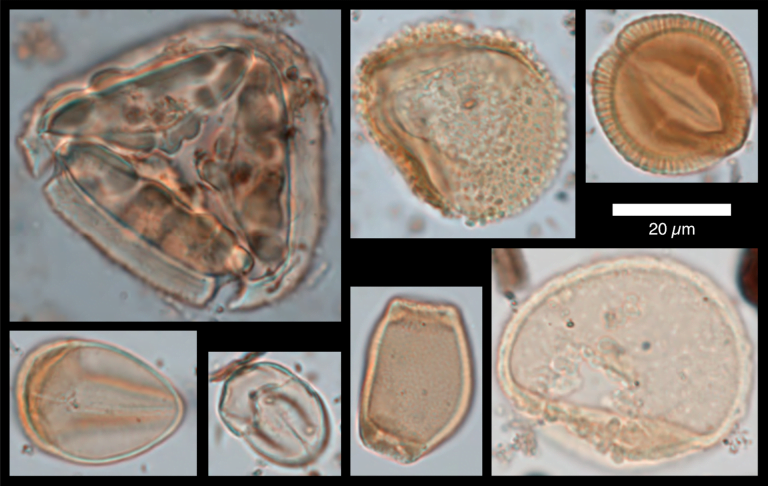

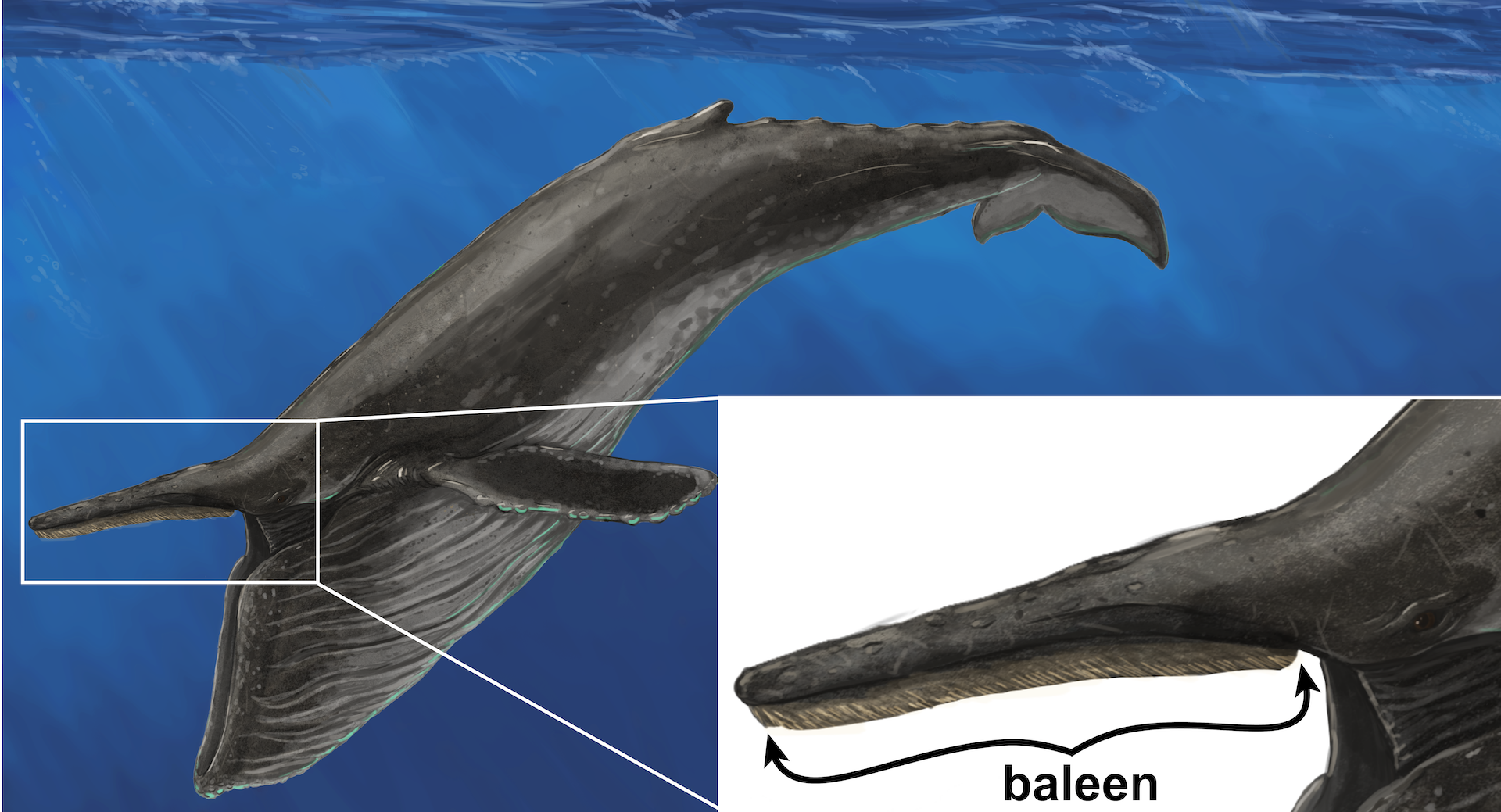

Most mammals have teeth in their mouth. Baleen whales are a strange exception. While their ancestors had teeth, today’s baleen whales instead have baleen – a large rack of fine, hair-like keratin used to filter out small krill from the water.

This structure enabled baleen whales to feed efficiently on enormous shoals of tiny zooplankton in productive parts of the ocean, which facilitated the evolution of larger and larger body sizes.

Art by Ruairidh Duncan

The ‘missing years’ of whale evolution

Various groups of toothed whales terrorised the ocean for millions of years, including some that were the ancestors of the toothless baleen whales. Yet at some time between 23 and 18 million years ago these ancient “toothed baleen whales” went extinct.

We aren’t exactly sure when, as fossil whales from this episode in Earth’s history are exceedingly rare. What we do know is immediately after this gap in the whale fossil record, only the relatively small, toothless ancestors of baleen whales remained.

Art by Ruairidh Duncan, graphic by Rob French

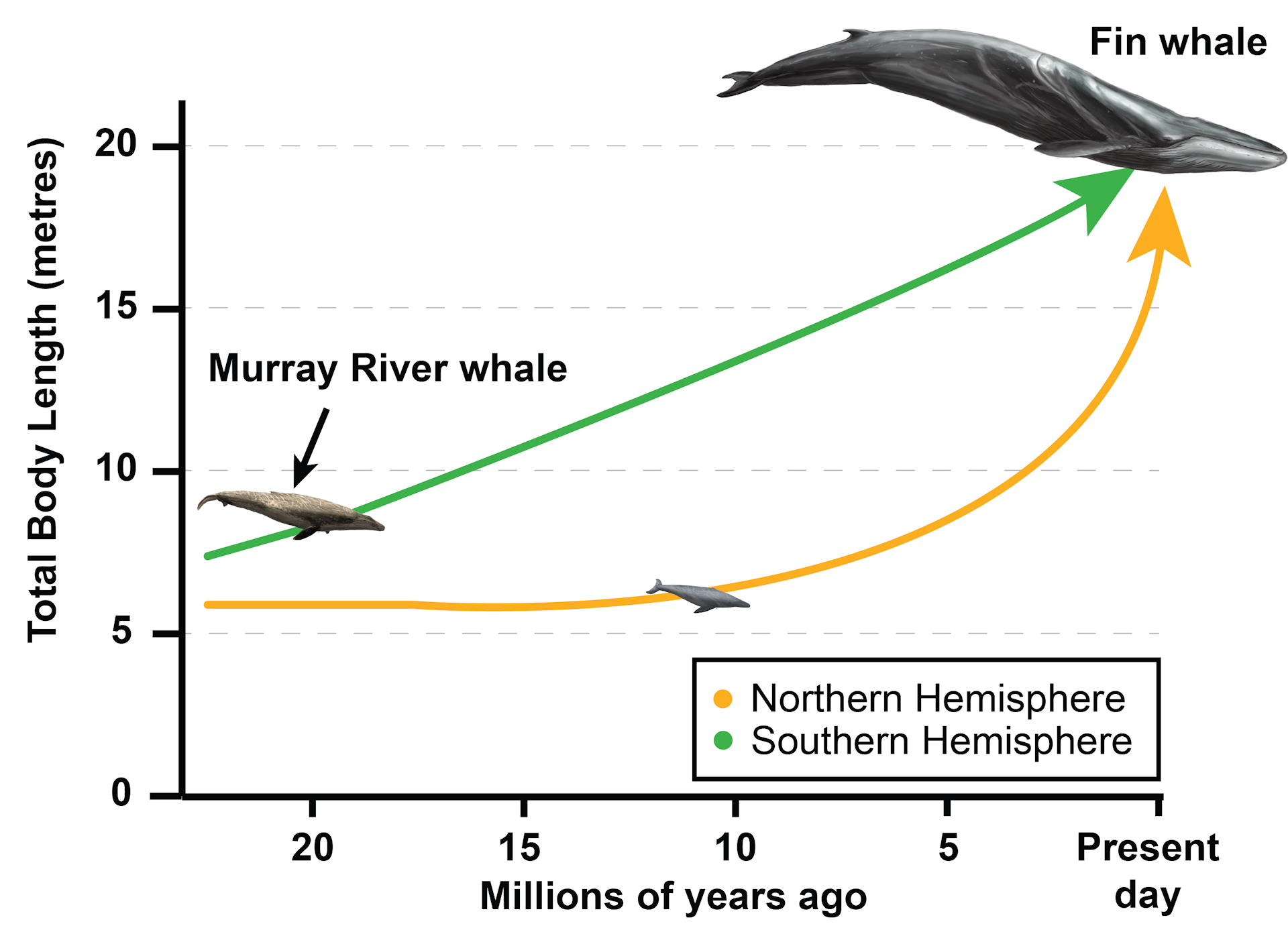

Scientists previously thought baleen whales kept to relatively small proportions until the ice ages (which began from about 3–2.5 million years ago). But the majority of research on trends in the evolutionary history of whales is based on the reasonably well-explored fossil record from the Northern Hemisphere – a notable bias that likely shaped these theories.

Crucially, new fossil finds from the Southern Hemisphere are starting to show us that at least down south, whales got bigger much earlier than previous theories suggest.

An unexpected find

More than 100 years ago, palaeontologist Francis Cudmore found the very tips of a large pair of fossil whale jaws eroding out of the banks of the Murray River in South Australia. These 19-million-year-old fossils made their way to Museums Victoria and remained unrecognised in the collection until they were rediscovered in a drawer by one of the authors, Erich Fitzgerald.

Using equations derived from measurements of modern-day baleen whales, we predicted the whale this fossilised “chin” came from was approximately nine metres long. The previous record holder from this early period of whale evolution was only six metres long.

Together with other fossils from Peru in South America, this suggests larger baleen whales may have emerged much earlier in their evolutionary history and the large body size of whales evolved gradually over many more millions of years than previous research suggested.

Art by Ruairidh Duncan, photo by Eugene Hyland

The Southern Hemisphere as the cradle of gigantic whale evolution

The large whale fossils from Australasia and South America seem to suggest that for most of the evolutionary history of baleen whales, whenever a large baleen whale shows up in the fossil record, it is in the Southern Hemisphere.

Strikingly, this pattern persists despite the fact the Southern Hemisphere contains less than 20% of the known fossil record of baleen whales. While this is an unexpectedly strong signal from our research, it doesn’t come as a complete surprise when we consider living baleen whales.

Today, the temperate seas of the Southern Hemisphere are connected by the chilly Southern Ocean, which surrounds Antarctica and is extremely productive, supporting the greatest biomass of marine megafauna on Earth.

Art by Ruairidh Duncan

Around the time baleen whales started evolving from big to gigantic, the strength of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current was intensifying, eventually leading to the present day powerhouse Southern Ocean.

Today, baleen whales are ecosystem engineers, their huge bodies consuming tremendous amounts of energy. Upon death, these whales provide an abundance of nutrients to deep-sea ecosystems.

As we learn more about the evolutionary history of whales, such as when and where their large size evolved, we can begin to understand just how ancient their role in the ocean ecosystem may have been and how it could shift in tune with global climate change.

Read more:

The true origins of the world’s smallest and weirdest whale

![]()

James Patrick Rule currently receives funding from an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council UKRI Fellowship, and previously received funding from an Australian Research Council Discovery Project.

Erich Fitzgerald received funding from an Australian Research Council Linkage Project that supported part of this research.